Author: Ed Nelson

Department of Sociology M/S SS97

California State University, Fresno

Fresno, CA 93740

Email: ednelson@csufresno.edu

Note to the Instructor: This exercise uses the 2014 General Social Survey (GSS) and SDA to explore the concept of spuriousness. SDA (Survey Documentation and Analysis) is an online statistical package written by the Survey Methods Program at UC Berkeley and is available without cost wherever one has an internet connection. The 2014 Cumulative Data File (1972 to 2014) is also available without cost by clicking here. For this exercise we will only be using the 2014 General Social Survey. A weight variable is automatically applied to the data set so it better represents the population from which the sample was selected. You have permission to use this exercise and to revise it to fit your needs. Please send a copy of any revision to the author. Included with this exercise (as separate files) are more detailed notes to the instructors and the exercise itself. Please contact the author for additional information.

I’m attaching the following files.

- Extended notes for instructors (MS Word; .docx format).

- This page (MS Word; .docx format).

I’m attaching the following files.

Goals of Exercise

The goal of this exercise is to explore the concept of spuriousness. We will consider the relationship of religiosity and how respondents feel about controlling the distribution of pornography and test for the possibility that this relationship is spurious due to sex. The exercise also gives you practice in combining categories of a variable (i.e., recoding) and using CROSSTABS in SDA to explore relationships among variables and to test for spuriousness.

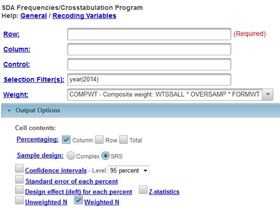

Part I—Religiosity and Control of the Distribution of Pornography

We’re going to use the General Social Survey (GSS) for this exercise. The GSS is a national probability sample of adults in the United States conducted by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC). The GSS started in 1972 and has been an annual or biannual survey ever since. For this exercise we’re going to use the 2014 GSS. To access the GSS cumulative data file in SDA format click here. The cumulative data file contains all the data from each GSS survey conducted from 1972 through 2014. We want to use only the data that was collected in 2014. To select out the 2014 data, enter year(2014) in the Selection Filter(s) box. Your screen should look like Figure 12_1. This tells SDA to select out the 2014 data from the cumulative file.

Figure 12-1

Notice that a weight variable has already been entered in the WEIGHT box. This will weight the data so the sample better represents the population from which the sample was selected.

There’s one other thing that it’s important to do. Click on the arrow next to OUTPUT OPTIONS and look at the line that says SAMPLE DESIGN. On your screen COMPLEX will be selected. Click on the circle next to SRS to select it.

The GSS is an example of a social survey. The investigators selected a sample from the population of all adults in the United States. This particular survey was conducted in 2014 and is a relatively large sample of approximately 2,500 adults. In a survey we ask respondents questions and use their answers as data for our analysis. The answers to these questions are used as measures of various concepts. In the language of survey research these measures are typically referred to as variables. Often we want to describe respondents in terms of social characteristics such as marital status, education, and age. These are all variables in the GSS.

Let’s look at the relationship between the strength of a person’s religious affiliation and how a person feels about controlling the distribution of pornography. One of the variables in the data set is pornlaw. This question asks respondents what type of laws they think we ought to have regulating the distribution of pornography. Should pornography be illegal for everyone or should it be illegal only for those under the age of 18 or should it be legal for everyone? We can draw a parallel to laws governing the distribution of drugs such as cocaine (illegal for everyone) and laws governing the distribution of alcohol and tobacco (illegal only for those under a certain age). So it’s really a social control issue.

What is going to be our measure or indicant of religiosity? Religiosity refers to the strength of a person’s attachment to their religious preference. One of the questions in the GSS asks respondents how strong they consider themselves to be in their chosen religion. The response categories are strong, somewhat strong, not very strong, or they have no religious preference. This variable is reliten in the data set.

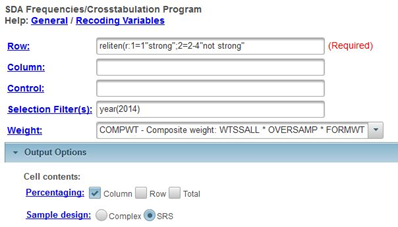

We’re going to recode reliten for this exercise. Recoding means to combine categories of the variable. Before we start recoding, run FREQUENCIES in SDA for the variable reliten so you will know what the frequency distribution looks like before you recode. The value 1 stands for those who say they are strong in their religious preference. We’re going to leave this category as it is. Then we’re going to combine somewhat strong (2), not very strong (3) and no religion (4) into one category and assign it a value of 2. Follow these steps to recode in SDA

- Enter the variable name in the appropriate row or column or control box. The variable name in this example is reliten. (Don’t enter the period.)

- After the variable name, enter (r: where r stands for recode.

- Enter the new value you want to assign to the first recode followed by the recode. In our case we want to assign the new value 1 to the old value 1 so this would be 1=1. (Don’t enter the period.)

- Enter the label you want to assign to this recode in double quotation marks so that would be “strong” followed by a semi-colon. So far our recode would look like this – reliten (r:1=1”strong”;. (Don’t enter the period.)

- Repeat this process for each recode. If you want to recode a range of values into a new value, it would look this – 2=2-4. (Don’t enter the period.)

- After the last recode, end the statement with a right parenthesis.

- This is what our recode statement would look like – reliten (r:1=1”strong”;2=2-4”not strong”). (Don’t enter the period.)

After you have recoded this variable, run FREQUENCIES in SDA for the recoded variable reliten. Your screen should look like Figure 12-2. Click RUN THE TABLE to produce the frequency distribution. Compare the two frequency distributions to make sure you didn’t make an error recoding. If you did make a mistake, you’ll need to do the recoding again.

Figure 12-2

Now that we’ve taken care of recoding reliten, let’s start by developing a hypothesis. A hypothesis states the relationship that you expect to find between your two variables. In this case, our hypothesis could be that the stronger a person’s religious affiliation, the more likely they are to feel that pornography ought to be illegal for everyone regardless of their age. However, the weaker the person’s religious affiliation, the more likely they are to feel that pornography ought to be illegal only for those under the age of 18. Imagine that you have told your hypothesis to a friend and your friend asks “Why?” You need to explain why you think your hypothesis is true. In other words, you need to develop an argument. What is the link between religiosity and the respondent’s opinion about pornography laws? Why should more religious individuals be more likely to think that pornography should be illegal for everyone? Write a clear argument explaining why you think your hypothesis is true.

Once you have developed your argument, then you should construct a dummy table showing what the relationship between the recoded variable reliten and pornlaw should look like if your hypothesis is true. Use “Tables” in Word to construct the table below. We’re going to always put the independent variable in the column and the dependent variable in the row. Add arrows to the table to show what your hypothesis would predict. For example, compare cells a and b. Would your hypothesis predict that cell a would be greater than cell b or would it predict that a would be less than b? Do the same thing for cells c and d. Does your hypothesis make any prediction about cells e and f? If it doesn’t, then don’t insert an arrow for these two cells. Copy the table below into your paper and add the arrows indicating the relationship that you expect to find.

|

Distribution of |

Recoded Religiosity |

|

|

Strong |

Not |

|

|

Illegal to all |

a |

b |

|

Illegal under 18 |

c |

d |

|

Legal |

e |

f |

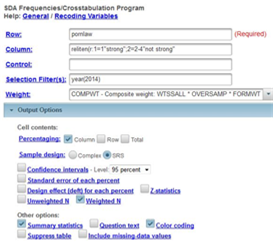

Now that you have constructed your dummy table, it’s time to find out what the relationship actually looks like. To do this you will need to run CROSSTABS in SDA. Be sure to put the recoded variable reliten in the column and the dependent variable pornlaw in the row. You also need to be sure to get the percents and the SUMMARY STATISTICS. Since the independent variable is the column variable, you will want the column percents. Your screen ought to look like Figure 12-3.

Figure 12-3

Click RUN THE TABLE to produce your table.

All that is left is to interpret the table. Since the independent variable is the column variable, we had SPSS compute the column percents. It’s important to compare the percents across. What does the table tell you about the relationship between religiosity and control over the distribution of pornography? Use the percents, Chi Square, and whichever measure of association you think is appropriate to help you interpret the table.

Remember not to make too much out of small percent differences. The reason we don’t want to make too much out of small differences is because of sampling error. No sample is a perfect representation of the population from which the sample was selected. There is always some error present. Small differences could just be sampling error. So we don’t want to make too much out of small differences.

Part II—Adding a Third Variable into the Analysis

At this point we have only considered two variables. We need to consider other variables that might be related to religiosity and pornography control. For example, sex may be related to both these variables. Women may be more likely to say that they are strong in their religion and women may also be more likely to feel that pornography ought to be illegal for all regardless of age. This raises the possibility that the relationship between self-reported strength of religion and how one feels about pornography laws might be due to sex. In other words, it may be spurious due to sex.

Let’s check to see if sex is related to both our independent and dependent variables. This is important because the relationship can only be spurious if the third variable (sex) is related to both your independent and dependent variables. Use CROSSTABS in SDA to get two tables – one table should cross tabulate sex and pornlaw and the other table should cross tabulate sex and the recoded variable reliten. Be sure to get the SUMMARY STATISTICS so you will be able to use Chi Square and whichever measure of association you think is appropriate. If sex is related to both variables, then we need to check further to see if the original relationship between religiosity and pornography control is spurious as a result of sex.

Part III—Checking for Spuriousness

How are we going to check on the possibility that the relationship between strength of religion and pornography laws is due to the effect of sex on the relationship? What we can do is to separate males and females into two tables and look at the relationship between strength of religion and pornography laws separately for men and for women.

We can do that in SDA by getting a crosstab putting pornlaw in the ROW box (our dependent variable), reliten in the COLUMN box (our independent variable), and sex in the CONTROL box. In this case, sex is the variable we are holding constant and is often called the control variable. You will get two tables – one for males and the other for females. Sometimes we call these partial tables since each partial table contains part of the sample.

Check to see what happens to the relationship between strength of religion and opinion on pornography laws when we hold sex constant. If the original relationship is spurious then it either ought to go away or to decrease substantially for both males and females. So look carefully at the two tables – one for males and the other for females. But how can we tell if the relationship goes away or decreases markedly for both males and females? One clue will be the percent differences. Compare the percent differences between those who are more religious (i.e., strong) and those who are less religious (i.e., not strong) for males and then for females with the percent differences in the original two-variable table. Did the percent difference stay about the same or did it decrease substantially? Another clue is your measure of association. Did the measure or association for males and females stay about the same or did it decrease substantially from that in the original two-variable table?

If the relationship had been due to sex, then the relationship between strength of religion and opinion on pornography laws would have disappeared or decreased substantially for both males and females when we took out the effect of sex by holding it constant. In other words, the relationship would be spurious. Spurious means that there is a statistical relationship, but not a causal relationship. It important to note that just because a relationship is not spurious due to sex doesn’t mean that it is not spurious at all. It might be spurious due to some other variable such as age.

Part IV—Conclusions

Summarize what you learned in this exercise. What was the original two-variable relationship between religiosity and control over the distribution of pornography? What happened when you introduced sex into the analysis as a control variable? Was the original relationship spurious or not? What does it mean to say a relationship is spurious?